A Chasm Grows in Brooklyn

“The gig and sharing economies give workers all the power to do what they want to do.”

– Ironic anti-union billionaire

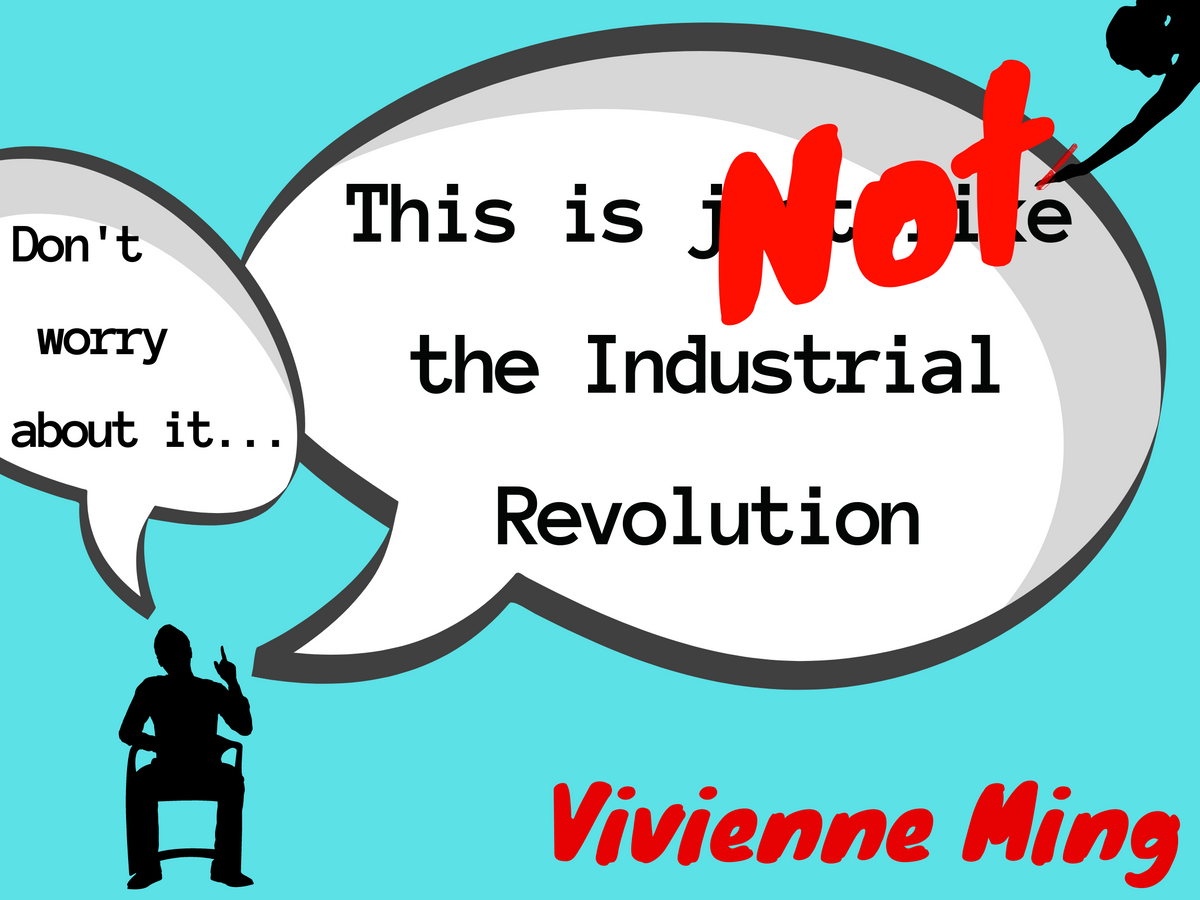

This is not the Industrial Revolution. Increasing job demand is becoming decoupled from labor supply, resulting in a growing chasm between the service and creative economies. Demand for creative labor (alone) doesn’t make people creative. AI and broader automation is deprofessionalizing high-skill labor, even as demand for creative labor increases. And despite the best efforts of nations and multinationals, upskilling and STEM training doesn’t change this reality.

While I’ve sought to offer a substantial body of evidence from psychological experiments, labor data, and economic models, any reasonable skeptic should wonder if explicit evidence of the chasm exists today. For this, we need only observe the talent practices at the cutting edge of the economy, the Tech industry.

At the same time that global Tech leaders battle for the most creative talent, they have built an entire infrastructure to distance themselves from the non-non workers that fill their service roles.

The divide between the service and creative economies driving the increasingly bifurcated demand represented way back in Fig. 4 isn’t some diffuse phenomenon at the scale of an entire economy. The divide increasingly plays out within the employee ranks of the most elite companies. At the same time that global Tech leaders battle for the most creative talent, they have built an entire infrastructure to distance themselves from the non-non workers that fill their service roles.

Beyond the internal practices at Google, Facebook, and Amazon, these human capital practices have fueled a new sector of the HR Tech market. Gig economy companies have emerged to fill the demand for routine labor at all skill levels, allowing employers to benefit from deprofessionalized labor while protecting them from “a bunch of culturally distinct, uneducated, unhappy unionizers.” The clearest evidence of the chasm is everyday life in Tech.

FAANG Bangers

In 2007 I gave a tech talk at Google on “efficient auditory coding using spikes”. The details of the talk don’t matter, and the specifics of the convolutional algorithm would excite about six people in the entire world. Geeking out at the Googleplex, however, was a real honor. Fresh from my doctoral research at CMU, being invited to give a talk at the hottest company in the world was a rather exciting ego stroke. Yet as excited as I was about the science and the venue, I didn’t realize that the most memorable part of the experience would be the food.

When I first arrived at the Googleplex (their ridiculously Seussian headquarters built atop the ancient ruins of Silicon Graphics), my host greeted me with a simple question, “Would you like a smoothie?”

Not yet intimately familiar with the math of diabetes, I of course said, “Hell, yes!” My host turned to a nondescript little window we’d been strolling passed and, like magic, I had a peach smoothie101. I’d arrived at the Big Rock Candy Mountain…for nerds.

It turns out that the sugar rush had a purpose as Google wisely kept their dour, socially-challenged research squad far away from the more neurotypical employees. By the time we finally arrived at the research building, my smoothie was done and it was time to talk about convolutional algorithms, sparse codes, and information theory.

Academic though it might all sound, the talk was genuine fun for me. When it was over, they took me out to lunch, which meant more free Google food in a different part of the research building. A group of chefs produced legitimately gourmet meals for the assembled Googlers. I vaguely recall a man in a chef's hat102 nearly begging me to enjoy the mahi-mahi he’d created. The entire spread confirmed all of the alluring stories of pampered excess I’d ever read about Google. (It remains one of the great regrets of my life that I was talked out of eating an organic, Google-branded Its-It103.)

In the years since, I’ve given many talks at Google, collaborated on research projects, and eaten much free food104. What I came to realize across those visits was that many of the staff with whom I interacted were a kind of reverse Cuckoo, substitute workers brought in to fill routine roles. Almost all of those meals were made, served, and cleared by people that worked right next to Googlers day-to-day, but employed by companies you’ve never heard of105. The security staffers manning the entrances and maintenance crews keeping the place running also didn’t work for Google, despite being onsite and indistinguishable to a casual visitor. They were all contract workers for third-party employers, in as a gig. Not Googlers, just Gigglers. And the Tech economy runs on the labor of Gigglers.

In 2019, Google had approximately 100,000 employees, but an additional 122,000 Gigglers kept the smoothies flowing and the bathrooms peachy. This large pool of contractors and temporary workers gives Google an enormous amount of human capital flexibility. During both the Recession of 2008 and our current pandemic, Google rescinded offers to contractors and temporary workers while largely preserving jobs for their full time employees. (I’ve done the same thing with interns and temporary workers at my own companies–bringing in a new employee is and should be a commitment106.) To their modest credit, Google recently pledged to ensure that all contractors, even when hired through a third party, receive at least $15 an hour. Yet with more contract workers than employees, Google is slowly digging their own internal chasm between service and creative, and the split is about much more than perks and benefits.

I was once a Giggler. A short time after my first visit to the Googleplex I began a collaboration on an audio search algorithm with one of their research groups. Though I was a research scientist at UC Berkeley, I was funded off of a grant supported by Google. The project itself was rather cool but also an education in the realities of scientific research inside industry. We were building a search engine for every sound on the internet. Type “Movie:Godfather gunshot” and receive every timepoint in The Godfather that included a gunshot. Or, just for fun, type “Donkey hysterectomy” and have nightmares for the remainder of your life.

The algorithm didn’t use tags or text analysis but rather analyzed the actual sounds themselves. You may note that no such service is available through Google today or, to the best of my knowledge, anywhere else. It turns out that the cost of running an algorithm for such a niche problem just didn’t appeal to any of the product teams at Google. As I’ve said before, I tend to invent broccoli for a world that wants peach smoothies.

My experience as an outside research collaborator is not uncommon at Google or many big Tech companies. For some like me who wanted to remain academics, having Google fund your research was an incredible privilege (not to mention all of the data that they can provide). But increasingly, those outside experts are just as much Gigglers as their lower-skilled contract “co-workers”. It’s not just the person who served my smoothie or the security guard who checked my credentials–even high-skill jobs are increasingly deprofessionalized into the Giggler labor pool.

Take, for example, computational linguists. This is a high-skill, highly educated population playing a crucial role in Google’s grand designs for AI language dominance. Yet unlike their fully employed co-workers, contract linguists at Google only make between $25-30 an hour. To understand why, consider the old AI joke107: “The performance of our speech recognition system got better every time we fired a linguist.” If you are a deep neural network engineer developing Google’s speech recognition and synthesis algorithms, I’m willing to bet that you are quite scornful of old school linguistic assumptions about how language works108. But it turns out that a lot of the grunt work of turning masses of raw data into a usable training corpus requires a large amount of preprocessing by teams of computational linguists.

Though these workers have university educations in the complexities of language, and not a few advanced degrees, their skills and knowledges are considered as routine as food service and custodial workers, and Google doesn’t want to employ non-non labor. They see these Giggling linguists as fully substitutable for one another–if a linguist left they would just hire another person to do the exact same job annotating datasets. Google is renting their rote knowledge rather than employing them as a creative value-add.

This is what so many don’t understand about work in the Tech industry: you don’t get a job because you know how to program, you get a job because you know how to solve problems. In fact, this is a misconception about Computer Science itself. CS is not the study of coding but rather the study of problem solving. If you were born in my generation or later and loved untangling problems (particularly if you had a certain inclination towards numbers) then learning Pascal or Python offered a powerful set of tools for those explorations. But learning to code was the result of that drive, not its cause. Knowing JavaScript is no more likely to secure a job at Google than knowing how to hold a paintbrush is likely to land me a gallery opening.

The correlation between STEM degrees and a highly paid career building technology that changes the world drives one of the core lazy myths of the future of work: teaching every kid to program will prepare them for the future. Programming is just a skill and like any other skill it is being automated. Unlike those Giggling linguists, an elite programmer at Google is perceived as unsubstitutable, not because she knows how to code, but because of how she uses that skill to uniquely explore the unknown. This is what makes her a creative value-add worth employing.

The difference between coding and problem solving explains one of the paradoxes of Silicon Valley, one I saw so clearly as Chief Scientist at Gild. The majority of the nearly 12 million programmers in our system were under- or unemployed at the same time that our elite Tech customers, like Google, were frantically searching for new talent. Gigglers were treated as a cost rather than a value-add.

A second profound assumption compels their investment in the expanding chasm: people can’t change.

Google’s right. The relative value of creative labor will only grow over time, and the creative-service split will increasingly dominate the future of work109, in Tech and beyond. But the split alone doesn’t explain Tech’s policy response of increasingly partitioning its workforce; they could just as easily invest in growing their creative labor pool. A second profound assumption compels their investment in the expanding chasm: people can’t change. Tech is burdened with the myth of the A-player, and no company better articulates this than Netflix.

I love movies (if you haven’t noticed). My very first startup was a miserable failure of a film company called Hardrive Productions110. So, when I got a personal message from Netflix several years ago asking if I was interested in being their Director of Algorithms, I was both flattered and intrigued. Their algorithmic work dives all the way down into issues of casting and plot111 for their original productions, and I would love to dabble in that world again. You might be surprised that my single line response was, “Sorry, but this will have to be another in a long line of terrible career decisions. (I’d still love to visit and meet everyone, though.)” (I’d still love to visit and meet everyone.)

I enjoy a good geek session exploring convergence proofs and optimality assumptions for algorithms. I love poking around in giant datasets and becoming the first person in the world to know some secret hidden within them112. And as I said, I love a good movie. But none of those are why I do the work I do. I have had so many companies try to recruit me as a Chief Scientist with lines like, “We’ve got the biggest, gnarliest data pipeline problems.” All I can think is, “And who is this helping?” It’s rather astonishing how many people have tried to recruit me for a C-Suite role with no evident knowledge of who I am or what makes me tick. I love a good movie, but I did not want to spend five years making movie recommendations.

My only other interaction with Netflix was a rather peripheral one shared with many in the industry. It was a notoriously blunt HBR article, “How Netflix Reinvented HR”. Patty McCord, former Chief Talent Officer at Netflix, shared numerous stories exploring the chasm between “A-players” and everyone else. “The best thing you can do for employees,” she wrote, “A perk better than foosball or free sushi–is hire only ‘A’ players to work alongside them.”

For the Tech industry, this isn’t just about salaries; it’s cultural: keep your non-nons away from my creatives.

In one example, she illustrates A-player culture with a story of a “top engineer” who was more productive working alone than with a whole team under him. To her, this revealed how “merely adequate” employees dragged down the culture and therefore the excellence of Netflix. For the Tech industry, this isn’t just about salaries; it’s cultural: keep your non-nons away from my creatives.

It might be hard to imagine how a “10x113” engineer was better off alone than working with three highly qualified employees that had all passed intensive tech interviews to land those roles. An alternate moral of this story is that this engineer probably shouldn’t have been in charge of a team and that Netflix had failed to prepare him as a manager. If you’re Netflix, though, having to “manage” someone is the failure. The power of their HR brand, and that of other elite Tech companies, means they can select exclusively from the creative complementarity side of the chasm. The large numbers of unemployed engineers in an industry desperate for talent isn’t a labor market failure. Big Tech knows those potential workers exist–they just don’t want to put in the effort to develop their capacity. Natural A-players only.

Like Google, Netflix has recognized the growing chasm. And like Google, they have chosen to dig in.

Learning to love the chasm has become the HR strategy for Google, Netflix, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, and nearly every tin-plated startup founder hoping to strike gold. This relationship with talent can even be found in stories of gourmand rodents and middle-aged superheroes produced by the Bay Area’s hometown movie studio, Pixar. In the wonderful Creativity Inc., the studio’s co-founder and president Ed Catmull reflects on the founding of Pixar. He presents a compelling argument of how its cultural roots–Steve Jobs, Lucasfilm, supercomputing, and the Pixar Braintrust–gave rise to one of the most successful blendings of art and industry in modern history. It doesn’t require a deep reading of Catmull’s book to notice that he and Patty McCord share very similar feelings about protecting A-players from the “merely adequate”.

Even a rat dreaming of becoming a chef can rise to the top in Tech.

If you don’t want to read Ed’s book, just watch the movies. In one of Pixar’s most underrated films, Ratatouille, we are told, “Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere.” This sentiment blends inclusive idealism with “meritocratic” elitism. It captures a dominant and self-congratulatory attitude felt throughout the industry. Even a rat dreaming of becoming a chef can rise to the top in Tech. The rest of the kitchen staff, however, are non-nons–highly skilled, and yet so substitutable that a horde of trash-munching rats could replace them. (Is there perhaps a self-aware humility in the human hero's completely undeserved upward trajectory? Linguini rivals Harry Potter as an icon of essentialist cultural transmission.)

Where Ratatouille’s message could be considered subtle, The Incredibles was basically written by Ayn Rand. The superheroes with natural powers (100x A-players) are being held back by a society fearful of exceptionalism, but in the end, only these elites can save non-nons from themselves. The main villain has no natural superpowers, only the tragic conviction that people are more than a collection of innate abilities. I truly enjoy the movie, but posing “everyone could be super” as a statement of supervillainy might even make Patty McCord blush.

You don’t need to spend much time in Silicon Valley to meet CEOs that think they’re a hero in an Ayn Rand novel or coder bros that think they’re Mr. Incredible. Some economists have even taken to calling elite companies “superfirms'' and suggest that their outsized success is due to “intangible capital114”. This latter idea refers to the hard-to-measure intellectual and organizational capacity present in creativity-dependent industries. Before deep learning or other modern AI technologies existed, the Tech industry was already benefiting from the productivity boost of creative complementarity. More than just hiring creatives, these organizations obsess over creating cultures that complement creative capacity.

There’s an old adage in internet culture that 1% of users generate all of the content, another 9% comment and share, while the remaining 90% just consume115. For Facebook and other Tech companies, this also explains their relationship with talent. If you are a hyper-competitive superstar firm, you will hire that 1% because they are the only ones for whom your intangible capital will induce creative complementarity. Because the 1% can’t run the company and keep the bathrooms tidy at the same time, the other 9% are your contractor labor pool for all of your non-creative work. This arrangement allows Facebook to reap an astonishing $2.2M in profit for each full-time employee.

AI and other drivers of creative complementarity are fueling demand for elite creative labor, but unlike in industrial revolutions past, no additional qualified candidates will fill those jobs just because they exist. This isn’t the routine labor of an 1890’s factory line or a 1980’s HR department. Just four metro areas116 produced the majority of the tech job growth in 2019, and one-third of the nation’s innovation jobs reside in just 16 counties. Tech firms simply cannot find the necessary density of creative labor outside certain metros117, and remote work won’t dramatically change this. Facebook sells a “democratizing” vision of the world, but internally they are wildly elitist118. And anything less threatens their long-term existence. Much like insurance companies that might publicly deny climate change while quietly pricinging it into their policies, the Tech industry talks up connectedness while firewalling themselves off from the non-non masses.

If people truly cannot change, those that benefit from creative complementarity get hired119, and everyone else must be segmented off.

If people cannot change then the Tech industry understands the chasm very well. They understand that in a creative economy an employee’s value is the thing that makes them unique. They understand that there is a finite creative labor pool to fill a growing demand. They understand that non-nons erode precious intangible capital. And they understand that AI will only exaggerate this divide. If people truly cannot change, those that benefit from creative complementarity get hired119, and everyone else must be segmented off.

Google, Facebook, and Netflix need Gigglers for all of the behind the scenes work that keeps their companies functional. Amazon’s reliance on Gigglers is existential. Literally every day I see an Amazon van driving around my neighborhood delivering packages. In the United States, 85% of Amazon’s 810,000 “employees” are in warehouses earning $15 an hour, and those labor metrics don’t even include their 500,000 delivery drivers120. Like Wonka and his Oompa Loompas, Jeff cannot deliver treats to the world without his Gigglers.

For many pundits, Amazon’s relationship with its warehouse and logistics workers evokes a classic debate of minimum wage and workers’ rights, but in fact, Amazon’s relationship with this workforce is much more reflective of the complexities of the chasm. As evidence of this, I offer the best job pitch I’ve ever received, “In seven years, we will be a one million person company, and your job will be to make their lives better.”

The leadership team at Amazon came across my work at Gild and had the rather demented thought, “What if we hire a mad scientist to run benevolent experiments on all of our employees to help improve their lives?” I don’t know if the job ever had a title, but I like to think of it as Chief Scientist for People. I would get to do the sort of research I do philanthropically at Socos Labs but at the scale of Amazon. If I can make a million people’s lives better, how could I say no? Frankly, I’d pay for the privilege.

When I visited Seattle to discuss the offer, I learned that one profound question separated us: can people change? It became clear very quickly that Amazon believes they can’t. And if they can’t, why trap them in dead-end jobs where they’ll never get a promotion and they’ll never get a raise? They saw a few years of work in their warehouse like a tour of duty in the army with GI Bill-like incentives waiting at the end. Their workers would make a decent wage121 for a few years, Amazon would get a bunch of packages delivered, and then they would part ways with training and education programs as thank you gifts.

The leadership’s assumption that people can’t change means that these workers are a fixed benefit with a cost that slowly increases with time, like a car whose maintenance cost exceeds its resale value. Stuck in a dead-end job, workers become unhappy, file workers comp. claims, and agitate for unionization122. Much like Netflix, Google, and the other Tech companies, Amazon saw these Gigglers as a cultural and financial liability. So when Amazon said that my job would be to make people’s lives better, they truly believed that it would be better to help them happily choose to leave after a couple of years and seek their fortune elsewhere.

If people can’t change, Amazon makes a compelling case. It may sound harsh, but for them to operate at the levels they have achieved, there’s simply no space for a lifelong career in their warehouses. If your labor is entirely substitutable, why would any company pay you more for the same task based on ideas like seniority or service? If they are right and people can’t change, their response to the chasm is rational123.

But what if they’re wrong? What does it take for a delivery driver to move into a creative job at Amazon? I had so many ideas for experiments to run on Amazon’s one million employees (1.2 million as of today) with the goal of answering that question. In the end, my opportunity to run these experiments came with a different company.

Remember when it was the “Sharing Economy”?

When I first encountered ShiftGig, they were a gig economy company focused on supplying a flexible workforce for temporary staffing and hospitality events. If you got a hotdog at the Grateful Dead’s last performance at Soldier Field, it was a ShiftGig employee that put some relish on it. There was no aspiration for sophisticated STEM skills or elite management techniques–just a basic need by large clients to have a flexible labor supply show up on time and in the right uniform. In many ways, this was the very same population I had hoped to reach at Amazon. So, when a call came from their Chief Business Officer, a former colleague from Gild, I was immediately interested.

ShiftGig had reached out to me about being Chief Scientist with dreams of building an AI marketplace to match their ShiftGigglers with their clients. In its early days, ShiftGig saw themselves as an open marketplace with the power to bring people and jobs together, maximizing work flexibility. They quickly found, though, that most of the jobs posted by their large corporate clients were the lowest-skilled and most substitutable. These companies needed a way to externalize the human capital cost while still benefiting from routine labor.

Some of their clients suggested that it would be more convenient if ShiftGig could act as a middleman rather than a marketplace, filling the jobs directly with its own labor force. So, ShiftGig created an app where potential gig workers could sign up and receive basic vetting and training. Those that passed that initial vetting became W2 employees of ShiftGig. Their model was to recruit individuals that had little access to the labor market–struggling single moms, high school drop-outs, and deeply indebted, unemployed college grads–and give them simple, flexible jobs on a gig-to-gig basis. The main criteria for employment was reliability.

ShitGig isn’t unique; gig economy companies simply exploit externally what Amazon, Google, and Facebook exploit internally: the chasm. Uber and others prosthelytized the “sharing economy” in their early days, a nostrum for all the unused capacity—cars, rooms, and people—fallow across the economy. It was Kool-Aid sold by philosopher-king-founders. Notice how quickly “sharing” left Uber’s vernacular when they embraced the idea of replacing all of their drivers with autonomous AI cars124. The sharing economy went from religion to a trivia question nearly overnight.

It’s easy to criticize large gig economy companies for trapping their gigglers in low-quality jobs– I’ve certainly done my fair share of criticising over the years–but many of them claim that the flexibility of the gig economy creates a new set of opportunities for a workforce that is being left behind. At ShiftGig, I saw an opportunity to test this claim. So, even though I was a bit busy, I agreed to become an external executive and “distinguished scientist” at ShiftGig.

The ShiftGig experiment would help reveal the true impact of gig work on low-skill workers, but perhaps it impacts higher-skilled workers completely differently. The gig economy has grown into more than car sharing and dog walking for single moms without high school diplomas. Some of those debtor grads have some real skills, even if no one wants to offer them a 401k. So, gig companies entered the market to connect designers, programmers, and other professionals with flexible work. One of those companies, UpWork, built a platform for high-skill contractors to manage their work and find clients without necessarily having to run their own firm.

The problem for this new class of gig contractors is that the clients on the other side of the marketplace want a new logo designed or landing page coded as cheaply and easily as they can order an Uber. These higher-skill gig economy companies had invented the perfect engine for deprofessionalization: a modest demand for highly-skilled but largely routine work and an enormous supply of underemployed laborers to carry it out. As we’ve shown, the Service-Creative split in the economy is not just about skill or education. The skills marketed by UpWork are more sophisticated than ShiftGig or TaskRabbit, but the UpWorkers are still just Gigglers.

In gig work, the currencies are price and reliability, and everything else is substitutable.

To make matters worse for the supply, the professional middle class isn’t just competing with art school dropouts and coding bootcampers in their neighborhood. ShiftGig and Amazon may require local labor, but the very nature of modern professional work is that it can be done from anywhere. UpWorkers might be a design firm in Jakarta or a hacker collective in Odessa. In gig work, the currencies are price and reliability, and everything else is substitutable. It is the purest expression of the service economy.

It’s also good business. UpWork had announced their IPO around the same time I was working with ShiftGig. I reached out to talk about running the same jobs-as-growth experiments on their higher-skilled UpWorkers as we were planning for lower-skilled ShiftGigglers.

Network Effects

A common narrative in the gig economy is that it increases economic dynamism by providing new opportunities to people struggling within the traditional economy. The greatest pride at ShiftGig was when a ShiftGiggler was “stolen” away by a client for a full-time job. ShiftGig’s clients would never have brought in a young woman with no college degree or previous work experience, but when that same woman spent three months side-by-side with their full-time employees they asked her to stay. ShiftGig’s entire office would buzz for days every time this happened.

While stories like this were an enormous emotional lift at ShiftGig, anecdotes are not science125. Unlike Uber where a gig worker either drives or they don’t, ShiftGig has a hierarchy of job titles with increasing pay matching increasing responsibilities. If gig work provides that dynamic lift for workers, then ShiftGig’s internal pay ladder would be the perfect opportunity to track that growth. So, I had the data science team set about measuring the historical impact of gig work on the lives of ShiftGigglers. We made three important discoveries.

First, the flexibility of gig work is transformative for single mothers struggling with traditional employment. A common story for this population was an endless cycle of new job, family emergency, firing… new job, family emergency, firing. The ability to opt in or out of a specific gig or preset hours when they expected to be available freed these working moms from that cycle of trading off between family and work. Nearly a third of ShiftGig’s workforce came from this population and the majority of them would not otherwise have been able to earn a steady income.

Second, there was a wild disparity in work hours within the workforce. A very small number of ShiftGigglers captured nearly all the shifts, while the majority didn’t get any gigs and left the app. ShiftGig desperately wanted to bring more workers into their system, but unreliable workers meant clients would cancel contracts. So, the community service managers, who handled the relationship with the client, would horde shifts for the workers they knew were the most reliable126. Workers who joined ShiftGig’s network early captured all of the opportunities to demonstrate their reliability, making it difficult for new people in the network to connect to shifts.

Third, and most disheartening, after two years completing shifts for ShiftGig, workers’ average earnings increased by only $0.02/hour. While single moms found work they might never have had and a small number of ShiftGigglers landed full-time jobs, the majority of people in the network found themselves no better off than where they started. Despite its internal pay ladder, for the average worker the fabled dynamism failed to emerge.

Interestingly, the wild disparity in work hours mirrors a phenomenon I’ve seen many times across many domains: network capture. One of the clearest examples of this was at the MOOC giant, Coursera127. As they were searching for strategies to monetize their growing student population, one obvious market was job placement. More than 30,000 students enrolled in a single session of co-founder Andrew Ng's machine learning course. This is an enticing population for employers desperate to find talented data scientists and machine learning engineers. Internal research at Coursera had identified that the single best predictor of employment success for its students was their participation in online discussions. The best future employees by far started as peer tutors, answering other students’ questions about the course material. Coursera just needed to identify those peer tutors (using some of Andrew’s own natural language processing algorithms) and potential employers would pay them for recommendations.

In traditional education, those 30,000 students are spread across hundreds of courses, with two or three peer tutors emerging from each course. That means more than a thousand peer tutors to recommend to potential employers. In the massive social network of a MOOC, however, a tiny number of elite students capture the entire “market”. Where thousands might have been peer tutors before, 12 students captured the network in Andrew’s course. Others may have been capable of helping their peers and may have benefited from the well known educational impacts of being a peer tutor (even tutoring virtual students), but in a densely connected network, the rich got richer, just as with the reliable ShiftGigglers.

In the cases of ShiftGig workers and Coursera students, network capture lowered the total capacity of the system as the best and earliest captured all of the demand. As a result, shifts went unfilled and potent educational benefits of peer tutoring, along with lucrative job placements, went unrealized.

At least those 12 Coursera tutors were giving good answers. In noisy networks, where human capital is harder to assess, network capture can be driven by signals unrelated to the quality of work done. For example, the algorithms we developed at Gild to find the best software developers mined through enormous datasets on open source coding platforms and programming Q&A sites (e.g. GitHub, BitBucket, and StackOverflow). Just as with Coursera and ShiftGig, we found that a tiny number of programmers captured the vast majority of followers, upvotes, and other social signals. While recruiters used these signals to discover job candidates, our analysis actually found that social signals predicted almost nothing about quality of code or other job related ability. A ranking of developers by StackOverflow upvotes showed little relationship to human expert rankings of developers based on samples of code128. Not only did network capture lower the total capacity of the system, but the mechanism of capture was unrelated to the capabilities of the programmers. Large numbers of popular programmers wrote mediocre code, while vast numbers of competent programmers went unnoticed.

Within UpWork, network capture effects were even worse. Unlike ShiftGig where the most active ShiftGigglers had direct relationships with their community managers, there were no existing relationships between UpWork’s clients and their large global platform of designers and programmers. Just as with the noisy networks in GitHub and StackOverflow, social signals dominated network capture. This rich-get-richer effect has been seen in many real-world experiments. Otherwise equitable KickStarter projects see dramatic boosts in funding based on the presence or absence of a single initial pledge, and social signals produce profound and unpredictable distortions in music ratings based on random initial conditions. Even experts are not immune to these noisy network effects–scientists reviewing submissions to the prestigious NeurIPS conference showed minimal agreement on the quality of the research they had reviewed. It’s not a surprise, then, that UpWorkers that signaled well were hired preferentially and captured all the gigs.

(The absence of network effects among Uber and Lyft drivers is perhaps the clearest evidence that it is not an open market between drivers and passengers. Instead, Uber’s price-optimizing algorithm depends purely on supply and demand amongst entirely substitutable passengers and drivers. This algorithmic pricing also undermines the most idealistic claims of work flexibility. The Uber drivers that make the most money are those that let the algorithm determine their schedule. As a result, Uber’s own research shows that female drivers make less than men because their greater need for a flexible work schedule, supported by ShiftGig, was penalized by Uber’s pricing algorithm. It is the exact opposite of flexible: to maximize earnings, Gigglers must drive exactly when and where Uber’s algorithm dictates.)

As it was put to me, they had too many workers and not enough work. It just didn’t make sense to invest any more in the workers.

All of the lost capacity at ShiftGig and UpWork represented both immediate productivity loss from unfilled gigs, but even more importantly, a failure to actively grow the capacity of individual workers. I began designing algorithms to try and match the capabilities of individual ShiftGigglers and UpWorkers with new gigs to break through the network capture effects and noisy signals. I proposed a collaboration to test some of these algorithms inside UpWork. The goal was not only to give talented UpWorkers a chance to demonstrate their capabilities, but ideally to match them with gigs that would actually grow those capabilities. Unfortunately, growing the capacity of their labor pool was simply not a problem that UpWork was interested in solving. As it was put to me, they had too many workers and not enough work. It just didn’t make sense to invest any more in the workers.

Instead, UpWork and similar platforms have invested in technologies for conspicuous monitoring of worker behavior. Research has shown that transparently monitoring work improves performance and visibly attending to workers promotes broad increases in productivity. But notably, most of this research refers to highly routine labor in lower-skill populations, which is decidedly not the self-image of most UpWorkers. If nearly every aspect of launching a career is deprofessionalized by UpWork, how do you ever grow into a true creative professional?

As early career roles like clerkships or residencies are deprofessionalized, the pathways to creative careers disappear129. While UpWork focuses on design and programming, other platforms are expanding into mental health, financial consulting, and legal services. As we’ve shown, this deprofessionalization greatly expands the labor supply and makes these basic forms of these services available to many who may never have had access before130. By explicitly decoupling skill and creativity, however, the gig economy robs an entire generation of the opportunity to learn how to make complex creative decisions on its own and robs us all of their full capacity..

The idea that people can work some gigs, gain experience, and build toward a career is the bait of the gig economy bait-and-switch. Just like upskilling, research repeatedly shows that working for ShiftGig, Uber, and Upwork is treading water. And that’s not even the switch. The deeper problem with the gig economy isn’t that it creates low-quality jobs. (I can’t imagine who would prefer to work in a Frick cokemine over driving an Uber.) The problem is that it entrenches the chasm by economically, culturally, and socially isolating workers, and thereby fundamentally reducing socioeconomic dynamism across society.

Upskilling doesn’t work. People can’t change. The merely adequate contaminate. Culture is everything. The split is unavoidable. A-players only. This mix of fear and reality drives elite employers131 to desperately shield their intangible capital from the service economy. The entire elaborate labor infrastructure was built, not to bridge the chasm, but to reinforce it132.

While these trends might evoke visions of an Elysium-like future of a segregated society, there are obviously a number of non-dystopian alternatives. For example, strong unionization and collective bargaining might allow many workers in the service economy to share in the economic gains of elite firms. This is complicated by an employment landscape that legally distances elite companies from workers’ bargaining power, but it is still a strong vision for how to share the gains across the chasm.

Universal Basic Income (UBI) takes the opposite approach, decoupling work and dignity by simply paying people dividends for being part of a hyper-productive society whether you have a job or not. While UBI has been proposed as a solution to many societal problems, in this context, it is specifically meant to address AI-driven job loss. But as we’ve shown, job demand is increasing, not falling. Any UBI proposal must explain how it fulfills our need for greater human potential.

Dynamism across both sides of the chasm will plummet unless we reconceptualize work as growth.

My core criticism of many visions of UBI or strong unionization is that they often embrace the chasm just as strongly as “A-Players Only”. They implicitly commit to the idea that most people are incapable of contributing more than a strong back and the ability to follow orders133. The result is lost economic capacity and human potential, even as those elite employers discover that the supply of creative talent can't fill the growing demand. Dynamism across both sides of the chasm will plummet unless we reconceptualize work as growth.

ShiftGig and UpWork had unique visions but aspiration alone isn’t enough. A recurring theme in my entrepreneurial life is that you must take your deepest beliefs to their absurd conclusions. If your startup is selling the idea work might be growth, then you must go all in and engineer that growth into the system. If the gig economy is to add more value than just delivering boxes and meals, it must actively lift career outcomes by design. This was my goal with ShiftGig–work as lift–and it is real.

The collected works of Prof. Schlashenschlessen

“I didn’t hear your keynote but the problem with it is that ATMs actually created teller jobs.”

– Pompous Mansplainer134

The American Library Life Stories

Collection title: An Oral History of Automation

Interviewee’s surname: Camejo

Interviewee’s forename: Linda

Occupation: [retired] bank teller

Title: Mrs.

Sex: Female

Date and place of birth: 30 September 1955, San Antonio, Texas

Dates of recording: 28 November 2018

Location of interview: Interviewee’s home, San Antonio

Name of interviewer: Dr. Dirk Schleshenshelsns

Recording format: MP3

No. of recordings: 2

Total Duration (HH:MM:SS): 01:24:32

Additional material: N/A

[Part 1]

This is an interview with [Linda], 28th of November, 2018.

Prof. SS: …[indistinct] There, the device is recording. Let us away! For the record, can you introduce yourself, my dear? Name… occupation...the land of your birth?

Camejo: My name is Linda Camejo…I was born and raised in San Antonio. I’m retired now, but I worked as a teller at the bank near the river for many years. I took early retirement ten...no, fifteen years ago.

Prof. SS: Hmmm, yes, indeed. What led you to embrace an early retirement?

Camejo: I mean, I was perfectly good at my job but it really was a sort of dead-end career, which...it wasn’t always, you know, but we could see it coming from a long way off. The pay was good enough, I stuck around for a long time, but I just wasn’t going anywhere, in my job, I mean. When the ATMs came in it got pretty lonely.

Prof. SS: Do you mean that fewer customers were coming into the bank because of the advent of these machines?

Camejo: No, no, I mean, there were plenty of customers, but there were just fewer of us.

Prof. SS: Yes, I see, yes. When were these ATM machines first introduced into your bank?

Camejo: At our bank? I think, ‘79 maybe. It felt like one day, it came out of nowhere, and the next, every bank had them.

Prof. SS: So, Ms. Camejo, how did your job change with the introduction of the ATM machine?

[indistinct furniture shifting]

…at first it seemed pretty nice, a lot of those people that would wait in line for their whole lunch hour to deposit a check at the counter, I mean, they didn’t have to do that anymore. Standing there, waiting to get back to the office, you know, stuck behind someone who’s added a mid-day conversation to their deposit. So I’d be talking to some nice old guy, and the person behind them would be waiting, and then they didn’t have to, that was pretty nice.

But for me, to be honest, it was exhausting. Having those people come in and check a balance, deposit a check, with no chit chat…that was a little break in the day. Now everything was a conversation, and not because they needed it. It was still just little stuff. But it was little stuff with hand holding.

Prof. SS: You noted that the job “got lonely”, that there were fewer of you. I assume you mean fewer tellers, yes?

Camejo: Yeah.

Prof. SS: Fascinating, just fascinating. There is a splashy belief, you see, initiated by Eric Schmidt and…

Camejo: Who’s that?

Prof. SS: A businessman, the former CEO of Google, a self-proclaimed “job elimination denier”...there is a belief escalated by him and many others in the industry that ATMs created more jobs for tellers, like you. These “smartest guys in the room” tell us that ATMs didn’t automate your jobs away; they created more jobs. Is that your assessment, Ms. Camejo? What was your experience at your bank?

Camejo: I mean, it wasn’t like a bunch of robots just came in and took our jobs. But looking back, that is when everything seemed to change. At my bank, like I said, it got kind of lonely. They weren’t firing the tellers, but we were getting pushed out, moved to other locations...

Prof. SS: Please tell me, how many tellers worked at your bank before and after you noticed these changes?

Camejo: Well, our bank had over 20 tellers, at least when I first started. Within a few years of the ATM, that was cut in half. That’s what I mean by lonely…same bank, half as many of us…

Prof. SS: ...but you said they weren’t getting fired?

Camejo: No, they were getting moved! With the ATMs it was super cheap to open tiny little branches all over town, so they kept pressuring us to leave the main office and go work in these satellite offices instead, where there was no real prospect of promotion. I started my job with goals. I was going to be a loan officer, or a manager. When they opened up new branches all over and tried to shuffle us around...I mean, there was nowhere to go.

And then there were more lower skilled people being hired because the older employees, like me, didn’t want to leave their home banks. They wouldn’t have been hired before, they wouldn’t have been qualified to do my work. I used to obsess over making the bosses happy and was so stressed about speaking up in meetings. Those new branch employees didn’t care about any of that.

Exogenous motivation vs. JiffyLube Banking.

Prof. SS: The Bureau of Labor Statistics says that during the time that you worked at the bank, the number of bank tellers in the U.S. actually doubled. It certainly seems that ATMs were actually creating jobs. Did you feel like you were part of that growth?

Camejo: Sure, yeah, there was a lot of new hiring going on while at the same time there were so many fewer people at my branch. I understand that people were getting teller jobs but only if they were willing to go work as one of like, two people at a strip mall or something, a place where they had never bothered to put a bank before. Many people left because they didn’t want to move.

The trends in the BLS statistics reverse even as I conduct this interview. The previous growth cotemperous with ATM expansion turns into a precipitous decline. Indeed, the agency has projected that teller employment will plummet by 100,000 jobs over the next decade.

Prof. SS: So you wouldn’t say that ATMs created “new” roles, even if there were more jobs, per se?

Camejo: Well many of the people that had been with me at the bank moved to new banks, but we did the same work. Maybe it was a little more high-touch, but the same transactions. They needed fewer of us at my bank, but when I saw a customer it was for the exact same reasons. The job didn’t really change, and people who were not willing to move to new branches sometimes just lost their jobs. My branch just didn’t need as many of us doing the same old job.

Prof SS: Thought leaders such as Mr. Schmidt seem to suggest that, freed from routine work, your job had somehow changed, that you and our co workers were engaged in more value-added tasks. That this value-add increased demand.

Indeed, they claim this phenomenon appears in other industries. For example, electronic discovery software increased demand for paralegals and laser scanners increased the number of cashiers at…

Camejo: Hah, well, more isn’t always better. Like I said, there were more jobs, you know, at those strip mall branches, but they came with limited opportunities and were filled up by lower-skilled people. So yeah, we saw the same thing at the bank early on. Lots of new roles, fewer careers. They keep saying everything’s better, but it’s never better for me. My life didn’t get better. I didn’t get promoted.

Prof. SS: So you’re saying that ATM machines didn’t lift tellers up the value-chain of the bank? Your career wasn’t more creative as a result?

Camejo: I mean, I took the job because I thought I could move up. My parents worked incredibly hard to send me to college, first in my family...this was the promise. If they worked hard, if I went to college like I thought I was supposed to, and got a great job at the bank, then I would move up. But that was before the ATMs.

Prof. SS: There’s been much research showing that the number of college degrees for tellers has gone up significantly.

Camejo: Well, maybe more college graduates were getting hired because there were just more college graduates in general. Every job seems to require a fancy degree from a fancy school. You needed the degree just to get an interview, forget the promotion.

You know, when I first started, I actually took some night classes to get some experience in finance, thinking I could move up. It isn’t like there were a lot of female VPs at a bank in 1976, but there were none at any of the other places I could get a job. There was that one woman back east who became a VP in three years with an art degree, I think she started as a teller too. I mean, she must have given up so much, I couldn’t even imagine. But then again I bet she didn’t have my accent so…

Anyway, back then I thought the banks at least had a path to move up, right? Then after the ATMs, that path from the mailroom or the teller counter all the way to the top... the machines kinda clogged up the middle.

Prof. SS: What do you think it would have taken to have worked your way up despite all this?

Camejo: Like I said, there were just so few women in executive roles at that time–I didn’t see many women moving up, so why would I have been different? I mean, now there are women in VP roles, so maybe it would have paid off. But back then I sorta felt that those dreams were never going to come to anything and I just decided to be okay with that.

Young people today still make choices like this–it’s not just me! I could have tried to change all these things and still never know if it would have paid off. When we put the burden on people who need to put food on the table then they make the same choice, right, the choice that promises less blood and sweat and some stability. I’m stable now!

You’ve said a number of times that the ATMs changed things. The myth of the ATM is that it made your job more creative, that the banks started calling you the ‘customer relations team’. It doesn’t seem like you agree that your job became more creative.

Camejo: I mean, they called us ‘customer relations’ because the customers that came to the counter wanted the social stuff. Yeah, I chatted with customers and helped them with their deposits–I wasn’t exactly VP of marketing!

Prof. SS: Many of these thought leaders say that even though there is less cash-handling, the ability of a teller to work with clients and market interpersonal skills has become more important.

Camejo: Hah! How much do you think interpersonal skills really matter in the types of transactions we usually saw through? Sure, being friendly is important enough, but it wasn’t as if we were making any grandiose connections with our customers or upselling them into a mortgage. We just got the customers from A to B in as few steps as possible.

Prof. SS: Well that sounds rather perverse. Are you saying that the ATM machines made your days even more routine?

Camejo: We weren’t working on a factory line, but after you’ve been on the job for a little while, there wasn’t a lot new to be learned. We chatted with a lot of people, deposited their checks. Our bosses certainly didn’t see us as doing, what did you call it…creative work? One of them actually had us rehearse our greetings. If they didn’t even trust us to say hello, I guess it’s not really surprising that we weren’t getting promoted from behind the counter.

Prof. SS: It’s fascinating that you say that. In my modest studies, I’ve repeatedly come across the idea of a grand divide between the service economy—the work you’ve described—and the creative economy.

It seems like you started with the aspiration of putting in your time on the service side for the opportunity to move into the creative side of the business. But you just happened to embark on your career right as this new technology began wedging itself deeper into the divide.

Camejo: I was working really hard, right, I had just finished those finance classes. I turned down all their attempts to move me to those new branches because I sort of saw you could only get a promotion if you remained in the main office, you know? And I finally applied for that promotion. I wanted to be the first female executive at my bank, and this guy half my age was deciding whether I got promoted, and he just looked at me and said, “Lady, a machine can do the job you’re doing. We need someone who can solve problems, not someone who can smile for the customers.” And that was that.

The Modern Spontaneous Creative

“AI will create more jobs than it destroys. It’s just like the Industrial Revolution.”

– Pompous Mansplainer

You’re the CEO of a multinational with 100,000 employees, and AI truly is creating more jobs than it destroys. In fact, it doesn’t seem to destroy many jobs at all. Instead, technological deprofessionalization actually lifts demand at the lower end of the skills ladder (remember Fig. 3, from a million years ago?). This is the exact opposite of our original thought experiment. There are lost roles within your company as demand for expensive, high-skill-but-routine labor drops, but there are still many more low-pay, low-autonomy jobs available. Technically, those new jobs aren’t actually within your company–they are with a third-party contractor that fills your service economy needs. This arrangement gives you both greater flexibility and lower human capital costs for the same productivity. So, while those jobs have left your books, they still exist.

The good news is that your company isn’t staring at the 80,000 layoffs of low-skill workers from the original thought experiment (just a whole lot of outsourcing), but as revealed in Fig. 4, demand for elite talent across the entire creative economy135 seems unquenchable. Unfortunately, most of your 20,000 high-skill employees are no more qualified than their lower-skilled co-workers to fill this huge increase in demand. Their skills are sophisticated but entirely substitutable. Many predictions about augmented intelligence assume that cognitive automation boosts everyone equally, just as industrial automation boosted everyone during the Industrial Revolution. But as you now know, AI’s impact on routine labor is largely additive while its impact on creative labor is multiplicative. Whether AI or intangible capital,creative complementarity only augments creative labor. This isn’t 20% of your current workforce, or even 10%. That differential lift for the creative vs. the routine will dominate long-term trends in the labor market, and you’re left to figure out how a few thousand of people can fill tens of thousands of creative jobs136.

And there won’t be enough Archies, Steve Shirleys, or Grandpa Daimlers to go around. Most of your competition will settle for using AI to substitute for people. This strategy will quickly lower their human capital costs but at the price of their future capacity. In contrast, a small number of your most successful competitors have already learned the value of creative complementarity. They are your true competition, and the fight for that limited talent pool will be one of the defining features of the future of work.

Your company doesn’t need five times as many high-skill employees; it needs ten to twenty times as many creatives. At least with the myth of the 10x A-player, your HR department could leverage university degrees or professional social signals. Now, given everything you’ve learned about network capture, you’re left wondering if those social signals have been reducing the human capacity of your company all along. Network capture reinforces some of the worst habits of risk-averse hiring, and even worse, it limits growth opportunities for the majority of qualified individuals. These effects become even more pronounced in noisy networks, where cultural transmission137 crowds out spontaneous creatives.

How the hell do you fill all of those new roles if the existing talent pipeline is tapped out, upskilling is treading water, and the gig economy erodes dynamism? Those who’ve learned to love the chasm are right, and the lazy myths of the Industrial Revolution are wrong–people don’t become creative just because of free time, cheap technology, university degrees, programming, STEM skills, microloans138, market demand, or the Industrial Revolution. What’s truly perverse is how many people embrace the chasm and the lazy myths at the same time.

If you don’t believe that even a minority of your workforce can be retrained to fill those new jobs, you are in good company. Like most of the Tech industry, Walmart and Starbucks don’t, either. A growing number of companies believe so strongly that people can’t change that they pay large sums of money to ensure their non-nons happily walk away. This isn’t villainy; it’s an economic choice:

- If you see employees as a cost, don’t fill those roles at all–steal from your future capacity and substitute for everyone.

- If you’ve come to love the chasm, gear up for the talent war–every superfirm in the world is now your direct competitor.

- If you believe that people can change, build up where all others dig in–confront the uncertainty of creating creatives.

Creating Creatives

If you’ve followed my entire argument and have still chosen option 3, you’re mad. You’re right, but you’re mad. For nearly every other company in the world, it’s a choice between substitution or chasm, and the reason is clear: growing creativity is both uncertain and effortful. One recent neuroscience study showed that highly creative people must engage multiple large-scale brain networks at the same time, a fundamentally effortful tension. Is it really surprising that quick and easy solutions like upskilling or programming bootcamps can’t shift the very architecture of our minds. Yet while much of this chapter evokes dismal futures of work, there have been clues along the way that growing creativity is possible.

We mentioned Raj Chetty’s research on the long-term impacts of individual teachers on their students. Some teachers produce a dramatic lift in their students’ career outcomes by teaching them how to explore the unknown. Ironically, this increased creativity served the students throughout their lives even as their routine academic performance dipped slightly over the next year. We found other clues of a dramatic lift in creativity in the research on desirable schoolsor peer tutoring opportunities.

My own work on the pitiable StingeBot also revealed the possibility of nurturing creativity, even in adults. While the long term effects weren’t as dramatic as Chetty’s superteachers, StingeBot repeatedly and reliably increased older students’ resilience and perspective taking during essay writing. This hints that creativity itself is more complex and multifaceted than a single quality that you either have or you don’t139.

These four studies are only the tip of the iceberg. In upcoming chapters, we delve into a mass of research and projects whose explicit purpose is to grow creativity and human capacity. We identify underlying factors associated with creativity and interventions that can change them. These interventions share a set of common traits with Chetty’s supertachers and peer tutoring opportunities, traits that are missing in so many of the mythical “solutions'' above. Effective interventions are naturalistic–they are embedded in messy, real-world contexts. They are extended in time, requiring in many cases multi-year engagement. They are effortful for all involved. And as we will explore in detail, effective interventions must address multiple underlying factors, never satisfied to focus on single dimensions140.

Now that you know that option 3, creating creatives, is guaranteed to be long, effortful, and messy, you may be second guessing your selection. You can certainly understand why the incentives have favored chasms and lazy myths. But while the trends aren’t good, we still have a choice. This isn’t a thought experiment.

In work, we can redesign “jobs” with the explicit intention of lifting human capacity. In education, we can deeply integrate development of creativity’s underlying factors into project-focused skill and knowledge learning. And our effort can extend beyond the formal institutions of work and school. Experiences in the home and throughout communities have profound impacts on these same factors; they can be nurtured long before a child steps foot in the classroom.

We must also redesign leadership. The tradition of hierarchical leadership has been one of the greatest barriers to leveraging creative complementarity. What is the point of hiring amazing creative people and then simply telling them what to do. Creative complementarity must be leveraged between people (intangible capital and culture) to grow collaborative capacity. In my own companies and labs, I’m not focused on whether potential employees know how to program or the facts of brains or the nuances of machine learning–I can teach them all of that. I only care that we have ideas together that I would never have discovered alone. Here again, this is not the Industrial Revolution, and leadership designed to optimize a production line wastes creative capacity.

This isn’t just about AI or jobs. The factors underlying what I’ve been calling “creativity” are also causally related to positive long-term life outcomes: health, weath, and happiness. In the coming chapters, we’ll tell the stories of modern spontaneous creative problem-explorers, or as I call them, “fanatics”141.. We’ll rethink marshmallows and reveal how the early experiences of little kids guide life outcomes. We’ll consider novel ways of building purpose, and we’ll look at how social skills can be so much more than eldercare, how creativity is a lived experience, and how we truly can teach people how to learn.

AI’s impact is limited by human capacity, but more importantly, so are we.