Us vs Us

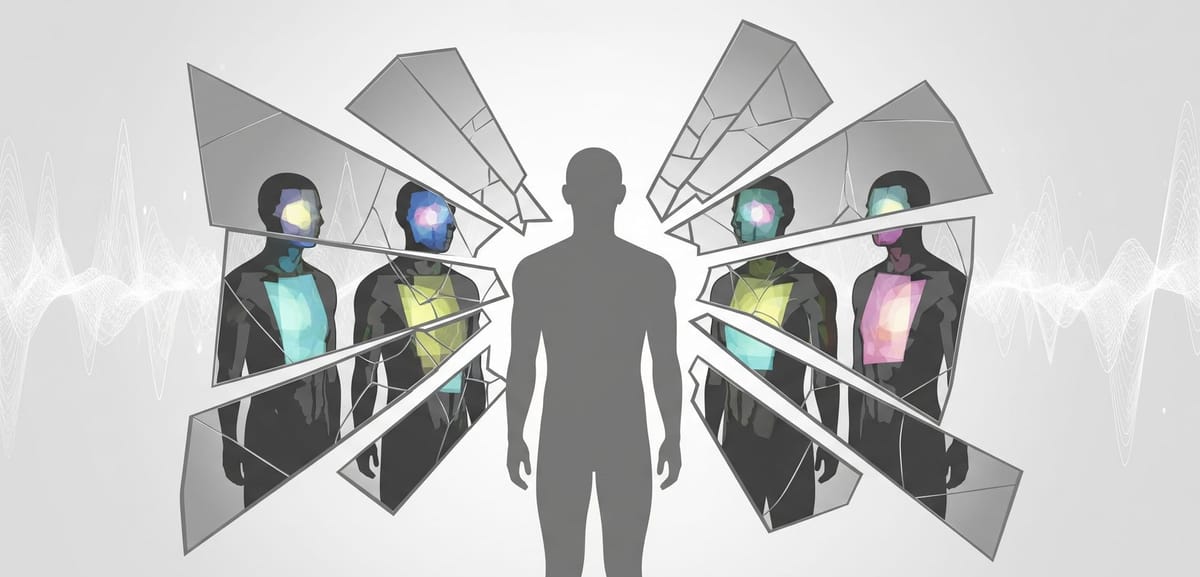

The deeply ingrained notion of a singular, stable self—a consistent "I" who navigates the world making rational choices based on enduring principles—is a powerful and comforting illusion. We perceive ourselves as unchanging entities and our decisions as a consistent internal compass. Yet, a growing body of research, including my own explorations into human behavior, paints a far more nuanced and, frankly, messier picture. We are less like enduring statues and more akin to a high-dimensional probability distribution, a wave function of potential selves held in superposition, each valid until the context of a specific moment collapses us into the version of "me" that makes that particular choice.

This "wave function" theory of self proposes that we are not one consistent individual, but rather a collection of context-sensitive personas, each sensitive to different situations. Our environment, social pressures, even our internal physiological state, can dramatically shift which "self" comes to the fore. Consider the stark contrast between intention and action in some of my experiments. Participants in a creative problem-solving challenge, when interviewed beforehand, almost universally recognized the strategic advantage of collaborating with strangers very different from themselves. They articulated sound reasons for this preference that were in fact consistent with the design of the task. Yet, the moment the experiment began, these same individuals almost invariably gravitated towards partners most similar to themselves, effectively abandoning their stated, rational strategy.

The truly fascinating part, however, isn't just the shift in behavior, but the powerful human drive to maintain the illusion of consistency. In post-experiment interviews, without fail, participants offered perfectly plausible, post-hoc explanations for their choices, retrospectively justifying why pairing with someone similar was, in fact, the optimal, or at least unavoidable, decision in that specific moment. Their subjective experience was one of unwavering consistency, even when their actions clearly demonstrated a dramatic shift in priorities driven by the immediate context of the experiment. Similarly, in a business war game, participants would identify unethical practices they swore they would never condone, only to deploy those very tactics when faced with time pressure and the watchful eyes of company leadership. Again, their post-hoc rationalizations painted a picture of consistent, if contextually adapted, ethical reasoning.

This phenomenon isn't unique to my lab; it echoes findings across cognitive science. Research on situational ethics demonstrates how good people can do bad things when contextual pressures (like authority or group conformity) overwhelm individual moral compasses. Studies on cognitive dissonance show our remarkable ability to alter our beliefs to align with our actions, thereby preserving that crucial sense of internal consistency. Even our motivations, as research on "state motivation" reveals, fluctuate dramatically day-to-day, powerfully influencing our decisions and effort, independent of our more stable "trait" personalities. The "self" that enthusiastically commits to a gym routine on Monday morning might be a very different "self" hitting the snooze button on a cold Tuesday, yet both feel authentically "me" in their respective moments.

The implications of the "wave function self” suggest that predicting behavior based solely on stated intentions or past actions can be remarkably unreliable without a deep understanding of the specific context in which future choices will be made. It challenges the very notion of a fixed "character" and instead emphasizes the dynamic interplay between our internal states and external environment. If we are a superposition of potential selves, then interventions aimed at changing behavior need to target not just the individual in isolation, but also the contextual triggers that collapse the wave function in a particular direction. Understanding this inherent variability and our powerful drive to perceive ourselves as consistent is crucial, not just for building better models of human behavior, but for fostering greater self-awareness, empathy, and perhaps even a more nuanced and forgiving understanding of ourselves and others.

Follow me on LinkedIn or join my growing Bluesky!

Research Roundup

Our Better Selves…in Retrospect

Are you trying to create change within your company or community? Your biggest hurdle might just be the human brain.

A series of experiments and surveys confirms that “psychological reactance to [new] system-level policies is greater when they are planned…than when they are already implemented…across various intervention contexts”.

Why is change less scary in retrospect? When considering a policy change, we “focus more on the transition-induced personal losses than on the prospective societal outcome gains”. However, our psychological resistance falls after change largely because “the salience of personal losses” decreases and “the salience of societal gains” grows.

The lessons for political campaigns, marketing focus groups, and even just personal growth are profound. We aren’t one unchanging person; we’re a wave function over many possible selves and many futures. Your choices choose you.

Eudaimonicly Smart

Does cognitive health make you happy? Does happiness make you smart? It depends on what kind of happiness.

A whole range of new findings establish the basic relationship:

- “older adults who started out with better well-being also had better cognitive function”,

- “sharper decreases in well-being were associated with sharper declines in cognitive function”,

- “better well-being on average had better cognitive function on average”, and

- “well-being change at one time point predicted subsequent cognitive change and vice versa”

But , it isn’t about spa days or self-care. This relationship between cognition and happiness was principally driven by “eudaimonic well-being and sense of purpose”, not simple “life satisfaction”. Meaning, purpose, and the sense of a job well done protect the brain…and that healthy brain helps create meaning and purpose.

If you want a better life, give it to someone else.

When Knowledge Isn’t Enough

Far too many startups and nonprofits think that information creates change. They all need a crash course on the whys behind people’s choices. (hint: it’s not a marketing problem—knowledge alone doesn’t do the trick.)

Take climate change. “Most people believe in human-caused climate change, yet this public consensus can be collectively underestimated”, and phenomenon known as “pluralistic ignorance”. For example, ”people across 11 countries underestimated the prevalence of proclimate views by at least 7.5% in Indonesia…and up to 20.8% in Brazil”.

So, marketing campaign…right? Unfortunately, “providing information about the actual public consensus on climate change was largely ineffective”. Slogans are not enough.

What might be the mechanisms of pluralistic ignorance? Here are a few of my guesses:

- Metacognitive Bias: people aren’t as pro-environment as they claim and so they (accurately) generalize those true beliefs to others.

- Subjective Under-Sample: the distribution of expressed beliefs is such that people systematically under-sample support for the environmental policy.

- Prospective-Retrospective Bias: People look at future change as less desirable and more costly than their assessment looking back after change. They implicitly generalize this bias as a source of uncertainty about the collective action of others. The additional uncertainty reduces generalization of support due (lost in noise).

As an interesting sidenote to those interested in cultural factors, “pluralistic ignorance about willingness to contribute financially to fight climate change was slightly more pronounced in looser than tighter cultures”. Tighter cultures might require greater social inference and perspective taking…or perhaps everyone just gives in to consensus more quickly.

<<Support my work: book a keynote or briefing!>>

Want to support my work but don't need a keynote from a mad scientist? Become a paid subscriber to this newsletter and recommend to friends!

SciFi, Fantasy, & Me

"Saturation Point” will be a movie. I’m not sure what to think of that, but perhaps more of Tchaikovsky's novellas (and novels) will find homes on film.

Stage & Screen

- September 18, Oakland: Reactive Conference

- Sep 28-Oct 3, South Africa: Finally I can return. Are you in SA? Book me!

- October 6, UK: More med school education

- October 29, Baltimore: The amazing future of libraries!

- November 4, Mountain View: More fun with Singularity University

- November 21, Warsaw: The Human Tech Summit

- December 8, San Francisco: Fortune Brainstorm AI SF talking about build a foundation model for human development

If your company, university, or conference just happen to be in one of the above locations and want the "best keynote I've ever heard" (shockingly spoken by multiple audiences last year)?

Vivienne L'Ecuyer Ming

| Follow more of my work at | |

|---|---|

| Socos Labs | The Human Trust |

| Dionysus Health | Optoceutics |

| RFK Human Rights | GenderCool |

| Crisis Venture Studios | Inclusion Impact Index |

| Neurotech Collider Hub at UC Berkeley | UCL Business School of Global Health |